A presentation to the Spiritual Reading Group given on the 15th of March on Powerpoint via Zoom by Cecily Clark. Edited by Philip Harvey. © Cecily Clark.

I would like to consider how an understanding of Wisdom and Folly in William Shakespeare and the Book of Proverbs can help us navigate our way through our world. We will discover similarities and differences between Wisdom and Folly in Shakespeare and Folly, and how they can enrich our own spirituality. By reading aloud some of the dramatized texts and discussion, it is hoped people will have a lived experience of Wisdom and Folly.

The Book of Proverbs. The Hebrew title misle, ‘proverbs of’, is an abbreviation of misle slomo, ‘the proverbs of Solomon’. Proverbs is a guidebook for successful living. Proverbs reveals how Israel’s distinctive faith affected their common life. The purpose of the book is to instruct the pupil about the worth and nature of Wisdom. It also warns the pupil about the dangers of Folly. Proverbs is a book about sowing and reaping; those who sow Wisdom reap life while those who sow Folly reap death.

There are three parts to the Book of Proverbs. (a) Chapters 1-16 The Proverbs of Solomon (1015-975 BC); these chapters appear to be unrelated without any grouping. (b) Chapters 17-22 The Words of the Wise (a collection of Israel’s sages). They are grouped by theme: regard for the poor, respect for the king, discipline of children, honour of parents, chastity. (c) Chapters 23-34 Additional Saying of the Wise; theme: social responsibility.

William Shakespeare (26 April 1564, Stratford-upon-Avon-23 April 1616, Stratford-upon-Avon) wrote 38 theatrical works, 154 sonnets, and two long narrative poems). The majority of his works were written between 1589 and 1613. The plays between 1600 and 1606 are considered to be his most biblical (Hamlet, Antony and Cleopatra, King Lear, Macbeth, Measure for Measure, Othello, Troilus and Cressida). Contemporary audiences are becoming more biblically illiterate and often miss his numerous biblical references, direct quotes or more attenuated.

In the Elizabethan era church attendance was compulsory. Shakespeare would have attended church regularly. He was also familiar with several Bible translations, especially the Great Bible of 1539 and the Geneva Bible of 1560. According to the scholar Emily Gray, there is also evidence that Shakespeare would have studied the Bible independently of compulsory church services.

Other influences on Shakespeare include the classical writers Cato, Cicero, Horace, Ovid (Metamorphoses), Plautus, Seneca, Terence, Homer (The Iliad), Hesiod, and Virgil. Classical Greek playwrights: Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. Plutarch (46-199 CE) was the Greek philosopher who was the source for his Roman history plays and the idea of the ‘tragic hero’. Petrarch (1304-1374) was the Italian poet who laid the foundations for Renaissance Humanism and influenced Shakespeare’s sonnets. Also the English poet Geoffrey Chaucer (1340-1400), Spagnoli of Mantua (1447-1516), and Erasmus, in particular his comic personification of Folly in ‘The Praise of Folly’ (1508).

Shakespeare

frequently “quotes or adapts biblical phrases with the specific purpose of

strengthening the audience’s emotional reaction and deepening their investment

in the dramatic storylines, making extensive biblical knowledge crucial to

experiencing the emotional and thematic richness of his works.” (Noble in Gray)

Further definitions: “When pride comes, then comes disgrace, but with humility comes wisdom.” (Proverbs 11:2) “Whoever fears the Lord walks uprightly, but those who despise him are devious in their ways.” (Proverbs 14:2)

In

‘As You Like It’, Shakespeare writes: “A fool thinks himself to be wise but a

wise man knows himself to be a fool.” Compare this with Proverbs 15: 2: “The

tongue of the wise commands knowledge but the mouth of the fool gushes folly.”

And here are more Shakespearean definitions of Wisdom and Folly:

“Give

every man thy ear, but few they voice.”

“How

far that little candle throws its beams! So shines a good deed in a naughty

world.”

“What’s

done can’t be undone.”

“This

above all; to thine own self be true.”

The

devil can cite Scripture for his purpose.”

“Sweet

mercy is nobility’s true badge.”

“Talking

isn’t doing. It is a kind of good deed to say well; and yet words are not

deeds.”

“Words

without thoughts never to heaven go.”

“All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players. They have their exits and their entrances; and one man in his time plays many parts.”

In Proverbs, Wisdom and Folly are personified. Interestingly, thy are all female characters. Lady Wisdom and Lady Folly are two examples. This makes an interesting link with Shakespeare’s theatrical characters because they too are shown to have personal features or characteristics.

Here

is a character of Wisdom in Proverbs 9:1-12

Lady Wisdom:

1. Wisdom has built her

house; she has hewn out its seven pillars.

2. She has prepared her meat

and mixed her wine; she has also set her table.

3. She has sent out her

maids, and she calls from the highest point of the city.

4. “Let all who are simple

come in here!” she says to those who lack judgment.

5. “Come, eat my food, and drink

the wine I have mixed.

6. Leave your simple ways and

you will live; walk in the way of understanding.

7. Whoever corrects a mocker

invites insult; whoever rebukes a wicked man incurs abuse.

8. Do not rebuke a mocker or

he will hate you; rebuke a wise man and he will love you.

9. Instruct a wise man and he will be wiser still;

teach a righteous man and he will add to his learning.

10.

The fear of the Lord is the beginning of

wisdom, and knowledge of the Holy One is understanding.

11.

For

through me your days will be many, and years will be added to your life.

12.

If

you are wise, your wisdom will reward you; if you are a mocker, you alone will

suffer.”

Characteristics

of Lady Wisdom:

Hard

worker.

Shows

good judgement.

Calls

and instructs the simple ones in understanding and wisdom.

Doesn’t

correct those who mock because they will retaliate.

A

wise person will accept correction.

A

wise person will increase in their wisdom and understanding through instruction.

Fearing

the Lord is Wisdom.

Knowledge

of God is understanding.

A

wise person prospers while a foolish one suffers.

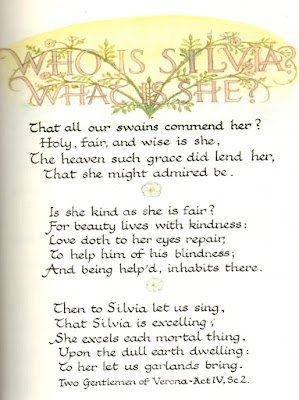

Comparing

Lady Wisdom with Silvia from ‘Two Gentlemen from Verona’. This play is a comedy

that centres on two pairs of lovers, Proteus and Julia, and Valentine and

Silvia. When the play begins, Valentine leaves Verona for Milan while his best

friend Proteus stays behind to woo Julia. Silvia. Daughter to the Duke and beloved

of Valentine, also sought after by Proteus and Thuria. Silvia commiserates with

Sebastian over the wrong that Proteus has done to Julia. She escapes her father’s

palace with the help of Sir Eglamour, who abandons her at the sight of the

outlaws.

Summary of Wisdom in Silvia:

Holy

and wise.

Shows

beauty in kindness.

Helpful.

Shows

humility even in success and popularity.

Shows

boldness but also loyalty.

Shows

morality and fidelity.

And

comparisons with Proverbs:

“Charm

is deceitful, and beauty is vain, but a woman who serves the Lord is to be

praised.” (Proverbs 31:30)

“Don’t

ever forget kindness and truth. Wear them like a necklace. Write them on your

heart as if on a tablet. Hen you will be respected and will please both God and

people.” (Proverbs 3:3-13)

“She

opens her mouth with wisdom, and the teaching of kindness is on her tongue.”

(Proverbs 31:26)

Wisdom

characters in Shakespeare are found, for example, in the paradoxical nature of

the tragic heroes – both noble and yet flawed. The flawed hero is biblical, consider

Moses, King David, and Jonah. Marcus Brutus in the play ‘Julius Caesar’ is

shown as ethical, patriotic, reasonable, and shows selflessness. Banquo in ‘Macbeth’

is shown as suppressing ambition.

Wisdom

in Folly. There is a range of fools in Shakespeare, purely for entertainment,

laughable, incompetent, mischievous. The purpose of the wise fool however is

that “they confound and confuse; they encourage speculation; they serve as

mediator between play and audience; they expose follies and faults in other

characters … The wise fools both mock and criticise the flaws of other

characters and of society; often, ‘in the laughter of fools the voice of wisdom

is heard.’” (Brudevold)

Continued

at (2)